[This article is the outcome of some great conversations and exchanges I’ve had recently with Jeremy Schulman (@nwkautomaniac) around automation and Devops in the world of networking. Thank you to Jeremy for those late tweaks before getting this posted! Thanks to Kirk Byers (@kirkbyers) as well - he was also gracious enough to respond to clarify a few things and assisted with this post indirectly.]

There have been numerous articles written that describe the what and the why of Devops. Reading through a few of these, you find references to CAMS — you’ll read how “Devops is about CAMS.” CAMS stands for Culture, Automation, Measurement, and Sharing. Imagine working in an environment where automation is embraced? We know most networks are not leveraging nearly any type of automation. While we usually talk about engineers (of all types) not embracing automation, is the harsh reality most organizations are from having the right culture to embrace automation?

What if there was a way to start testing network automation without taking a risk in a production environment? And to top it off, the network automation was being done using some of the same tools that are already being used by the Devops folks out there (not Jack’s custom script that no one else is aware of). There are four leading configuration management solutions being used by the Devops community – they include Puppet, Chef, Ansible, and Salt.

In this (long) post, we’ll explore the use of Ansible specifically for automating network device configuration taking a look at the what, why, and how.

Making the case for network automation and configuration management

Are you the kind of person that has to build out configurations? Maybe load OSs on new devices or maybe perform an OS upgrade once or twice per year? Maybe you need to quickly deploy a new change across several devices? And you wish you had a tool that offered customization that made it relevant for your environment, but didn’t require you to be a programmer? Too good to be true? Keep reading.

Here are three basic uses cases where network automation could lend a hand:

- Initial device configuration – ever have to unbox a bunch of new gear and configure each device individually? Maybe there was a bunch of copying and pasting between text files during this process? Ansible can be used for “network build automation” as Schulman likes to call it. This can be as simple as using Ansible to create the finalized text files for you and you still load them onto the devices or use Ansible for config building + deploying.

- Deploying configuration across one or more devices – this is when you’d want to deploy a simple change across the network. Or maybe you just need to update one device. It doesn’t matter – either can be done with Ansible.

- Workflow Automation – combine multiple network configurations and create custom specific workflows by leveraging one or more playbooks and even intregrate to workflows that include system and application changes. This is where Ansible really starts to show its power.

As an aside…as you start thinking about network provisioning and automation, think about tools built for network provisioning. Are there many out there today focused on bootstrap provisioning? Who’s to say one tool can’t be used to provision while a different tool is used when making general changes?

Why Ansible for Networking?

First and foremost, it’s the only configuration management tool of the four leading solutions that is 100% agentless. Being agentless simplifies management by eliminating the need to deploy and manage the agents. More importantly for those focused in the network space, most network devices are still “closed” in a such a way 3rd party software agents cannot be loaded onto the device. Note: While there are a variety of data center switching platforms that now support Puppet and Chef agents, there are many more that don’t, and remember there are plenty of devices that exist outside of the data center. This makes Ansible a solid choice to begin testing with. For what it’s worth, Ansible may or may not be the solution you end up deploying to production, but it’s less about the particular tool being used and more about the process, approach, and methodology.

Device Requirements for Ansible

While there are no agents with Ansible, there are still device requirements (maybe I’ll call them preferences). First, the device needs to support SSH. Ansible uses SSH to login to remote devices to execute changes. The second thing is the device needs to support Python. Ansible logs into the device, drops in an executable module (typically Python), executes it, and then removes the module. While this isn’t an agent, I like to think about this as a type of stub/temp agent, but in reality, it’s just a piece of Python code that is executed. This code, while usually removed, can be kept on the device if that’s needed for some reason. Thus, we can see the two main requirements for Ansible devices are support for SSH and Python. The reason I said these are more like preferences is that Python isn’t a hard-set requirement. If the device doesn’t support Python, it is still possible to leverage SSH and send CLI commands. It’s also possible to leverage a native device API such as using NETCONF, Arista eAPI, or Cisco onePK, etc. In these examples, it’ll take some back end work to develop the modules to make this happen though. On a side note, Jeremy is already working on this for Juniper devices.

Quick look at YAML and Jinja2

Before we get started diving into Ansible, Jjinja2 and YAML need to be covered. More funky names, I know. Since Ansible leverages YAML and integrates with jinja2 templates, they are important to cover though.

Jinja2

There needs to be a way to define configuration files as templates. As defined on the official jinja site, Jinja2 is a templating language for Python. I know I know, What the heck does that mean? Imagine you have a bunch of .txt files that have switch configurations. You need to update the NTP server in all of your files. What do you do? Clearly you can do it manually wasting precious time, or you can leverage Jinja2 templating with Python and change ‘ntp server 1.1.1.1’ to ‘ntp ’ in each of your text files. The templating language is syntax that occurs in the curly brackets in the actual template files that will still resemble general config files. This will make more sense below. In this example, you just need to make ntp_variable = 2.2.2.2 in one location to update all config files. We’ll see it in action with Ansible soon.

YAML

You need a place to store the variables that get merged into those Jinja2 templates. Sometimes that data is hierarchical or complex – it doesn’t always lend itself to an Excel spreadsheet or a CSV file. You don’t want to use XML, well because, who does, right? YAML is a great middle ground, and appears to be the defacto language used by most modern DevOps tools today. The great thing about YAML is that is natively imports into variables within the tools that you can access directly; so no writing code just to get at the data you want (like you have to do with CSV files or XML). Don’t worry, you’ll see YAML in action soon enough!

Now finally onto Ansible…

Please note I am not really going to cover the process of installing or running Ansible. I am going to focus on what Ansible is doing in a very specific use case/example. The example being used can be found at Jeremy Schulman’s github repo. Click the link for the ansible-vsrx-demo.

We’ll start by looking at the ‘baseconf’ playbook in the ‘ansible-vsrx-demo’ directory. This playbook is used to template-build a complete configuration file for each host defined in the “hosts” list. Each configuration file is assembled from of a series of configuration snippets (jinja2 templates). These snippet templates are located in specific Ansible “role” directories. In the case of this demo, there are two firewall roles: one that represents a “DMZ” firewall, and another that represents a “PCI” firewall. So this demo is a bit more interesting than just a simple “Hello, world” type example. You’ll get exposed to a number of real-world concepts that make Ansible great for us networking folks.

There are more files/directories in the demo than needed for purposes of this write up, but we’ll be looking at the directories called ‘group_vars,’ ‘host_vars,’ and ‘roles.’ Because this is where variables and template files are stored.

Ansible is all about “Playbooks” – think of sports teams – they need playbooks to hold all of their plays, right? By the way, this is where YAML comes into action too. Take a look at the picture below to see the high level overview of a playbook that includes the playbook itself, plays, and tasks. Roles, etc. are not shown here.

The picture below shows the contents of the baseconf playbook. Before we go through the playbook line by line, it’s important to remember this playbook automates the building of device configuration files — nothing more and nothing less, although Ansible can do a whole lot more!

Line 1: YAML documents always start with three dashed lines as such ‘—‘ ; it’s just something to accept and get used to.

Line 2: ‘-‘ denotes a “list” in YAML. Here it’s a list of one meaning there is one play in this playbook. ‘name: Create Junos BASECONF’ is a key/value pair and the value, ‘Create Junos BASECONF’ is displayed when the playbook is run. Very straightforward – it’s really just displaying text. Could come in handy when troubleshooting.

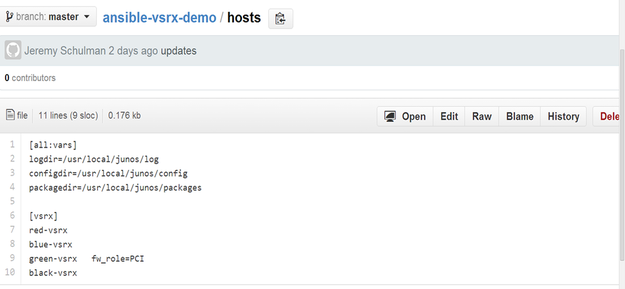

Line 3: ‘hosts: all’ Playbooks execute plays and the plays get executed on a given set of devices. The devices that will be included in this play are defined by using the key/value pair of ‘hosts: VALUE’ — in this example, all devices will be used. The hosts are defined in a file called hosts in the main ‘ansible-vsrx-demo’ directory. The file contents can be seen below.

In larger deployments, there can be multiple groups defined in the hosts file.

Line 4: “connection: local” is slick actually. It means the actions will be run local on the server running Ansible and not on the target host. This can be extremely useful when automating the building of network configurations, which is exactly what we are doing here! It’s also a good way to test.

Line 5: When Ansible connects to a device, it can gather some facts about the device automatically. The facts gathered will vary based on device type. Test this out do some searches on what this can provide back for your devices.

Line 7: pre_tasks aren’t required, but can be used for a way to execute tasks before roles are applied. Here, directories are being cleaned up and any prior files are removed.

Line 8: similar to line 2, this data will be displayed when the playbook is run.

Line 9: file is a built-in module in Ansible. It is used to set file attributes. Since ‘state=absent’ this is removing any directories.

Note: ‘configdir’ is a variable defined in the ‘hosts’ file in the main ‘ansible-vsrx-demo’ directory and ‘inventory_hostname’ is a built in variable that refers to the name given to the host in the hosts file. Remember these tasks are being executed for each host in the host file (remember line 3).

Line 10: register is a built-in module in Ansible. Register is used to store the results of individual tasks. Use of -v when executing playbooks will show possible values for the results. Results are being stored in a variable called baseconfdir.

Line 11: as already seen, this is used to display ‘create host-baseconf’ directory when executing the playbook

Line 12: we already know ‘file’ is used to set attributes. Here ‘state=directory’ and when this is set, the directory will be created

Line 14: roles: – roles are an important part of Ansible. This is where particular tasks and templates can be applied based on particular devices, etc.

Line 15: ‘baseconf’ as defined here is referring to a particular role. Details of this role can be found in /roles/baseconf. There are two main directories listed. They are tasks and templates. If you look in the tasks directory, there will be a main.yml file that will continue to execute tasks as part of this playbook.

As can be seen, this file is a playbook (in YAML) being called by the original baseconf playbook. This file is essentially building the network device configurations based on configuration templates. The pre-built template file is located at where item is a variable. Get used to the “” denoting a variable. The ‘with’ statement in line 4 essentially creates an iterator to loop through the elements in the /baseconf/templates directory. Since the templates directory has two templates, namely ‘00_interfaces.conf’ and ‘01_zones.conf’, the ‘with’ statement ‘loops’ through twice.

And by the way, these templates are Jinja2 based templates. Here is the output of the interfaces template.

This actually resembles that of a Juniper device configuration. For those only familiar with Cisco, this may seem a bit odd even without all the curly brackets. There are numerous variables that are used in the template.

Variables can be pulled in from several places actually in any given YAML file. There could be a /baseconf/vars directory to store variables (not used here) and there also can be ‘host_vars’ and ‘group_vars’ directories in the main directory where the initial playbook is. Additionally, variables can also be defined in host files! Needless to say, it could seem confusing, but it really offers flexibility based on design/deployment of what the goal is. I’m not going to look at the group_vars in greater detail, but they are used as variables for groups of devices. Jeremy does have a few of these defined if you want to take a look.

Go to the /host_vars directory and there will be four more YAML files that are defining variables for specific hosts. Remember when the ‘baseconf’ role is executed in the ‘basconf’ playbook, it is executed for each host because of ‘hosts: all.’ So, as each template is being created, the proper variables are being pulled from the proper /host_vars/* configuration YAML file.

Getting back to the templates – once they are generated, they are stored in the destination as defined in line 3 of the main.yml file. It’s worth pointing out that baseconfdir was the variable that stored the results of the ‘register’ module and baseconfdir is in fact a dictionary. ‘path’ was just a key in baseconfdir which was returned when ‘register’ was run. The last part of the destination is the file name, which is . Item here is the same as above, so it’s the full path to the template, but “basename” basically says, get the last name of the file path.

At this point, the baseconf role has been applied/executed.

Line 16 & 17: The next two roles are conditional. Feel free to dig around to see where the “fw_role” variables are stored.

Line 19-21: By now, I’m sure you can tell what is going on here!

Playbook Results!

Let’s take a look at the execution of this playbook. All I did was download the repo from github at Jeremy’s profile and run it (after installing Ansible, of course).

Notice all of the display lines in white color. These are where ‘name:’ is defined throughout the playbook. As you can see, it’s good for operational reasons. Everything should seem pretty straightforward. Note that a few tasks were skipped because the roles being applied were conditional. If the condition isn’t met, applying the role will be skipped.

As for the real test, let’s take a look at the directory with the templates created!

There are four directories created. Let’s look at the contents of one of them.

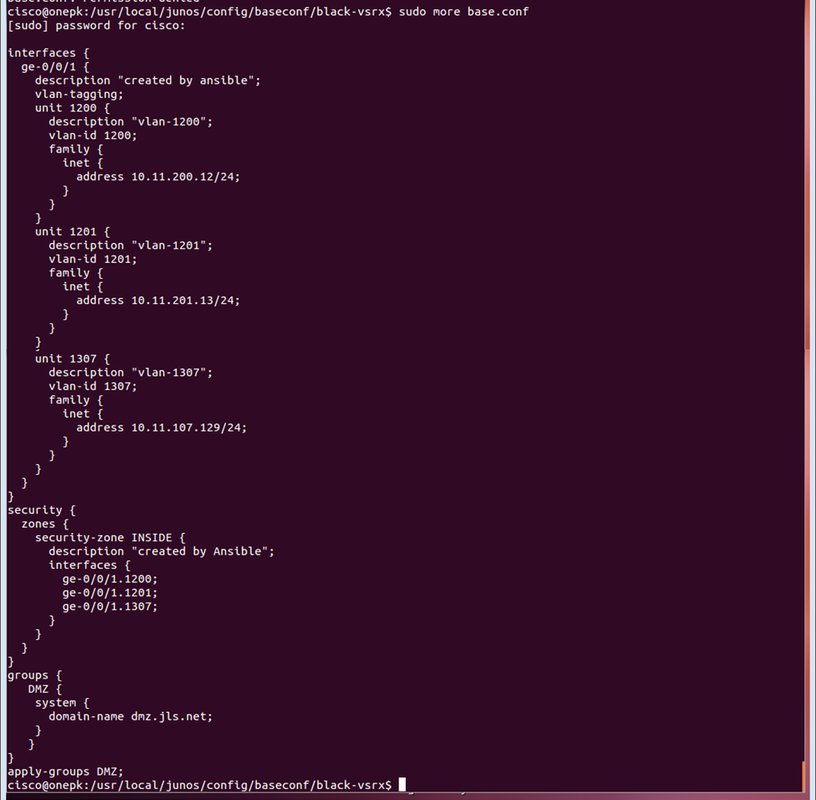

Take a look at the config files. The last post_task (line 21) was to assemble the configuration “snippets” into a final config file. Let’s look at the final config ‘base.conf’ for black-vsrx.

How about that? It worked. This config can now be applied to the device. A good hard look at using Ansible for automating the creation of network configuration files.

One more cool thing about this demo script is that the final config file is the compilation of snippets. This should tell you that it’s quite possible to automate the configs needed for particular tasks. This clearly doesn’t have to be used for only full blown configurations, but the reality is, there are devices deployed every day, and quite often they are being staged and configured manually.

Wrapping it up

Hope you can see from this one example, Ansible can prove to be pretty powerful and the network as a whole doesn’t have to be automated overnight. It’s about thinking a little differently and exploring some automation to see if it makes sense for any given environment. There are steps that can be taken to learn about these new processes and tools. And the best part is, all of these configuration management tools are open source and can be tried at no cost (there is usually a paid version). If you are talking to your network vendors (including load balancing, switching, routing, etc.) ask about these tools and see if they offer Python support (to execute Ansible modules) or better yet, see if they are creating their own modules to streamline the use of these tools even more!

Anyone else out there using Ansible for network configuration and automation? If so, let me know. Would love to hear more about it.

If this sparks any further ideas or raises any particular questions, I’m all ears. Feel free to comment below or write in directly to me.

And on a side note, if you’re interested in more formal Network Automation training that covers Ansible and Python, check this out: Network Automation Course Schedule. I usually teach most of the courses listed.

Thanks, Jason

Twitter: @jedelman8